What the backtracking of oil and gas climate ambitions means for corporate decarbonisation

Oil and gas companies’ efforts to position themselves in the net zero transition have always been perceived as somewhat counterintuitive. But their recent scaling back of climate ambitions, just as the sector prepares to take centre stage at COP28, is particularly controversial. So what is driving this backtracking, and how will it affect the sector and the world’s decarbonisation goals?

It’s no secret that the oil and gas sector is largely responsible for the crisis we find ourselves in. In 2022, the production, transport and processing of oil and gas emitted the equivalent of 5.1 billion tonnes of CO2. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), this is about 15% of all energy-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – and this number pales in comparison to the emissions generated by the consumption of oil and gas products. Last year, as the aviation sector continued to recover from the pandemic, emissions from oil consumption rose to 11.2 gigatonnes, or almost a third of the global energy total.

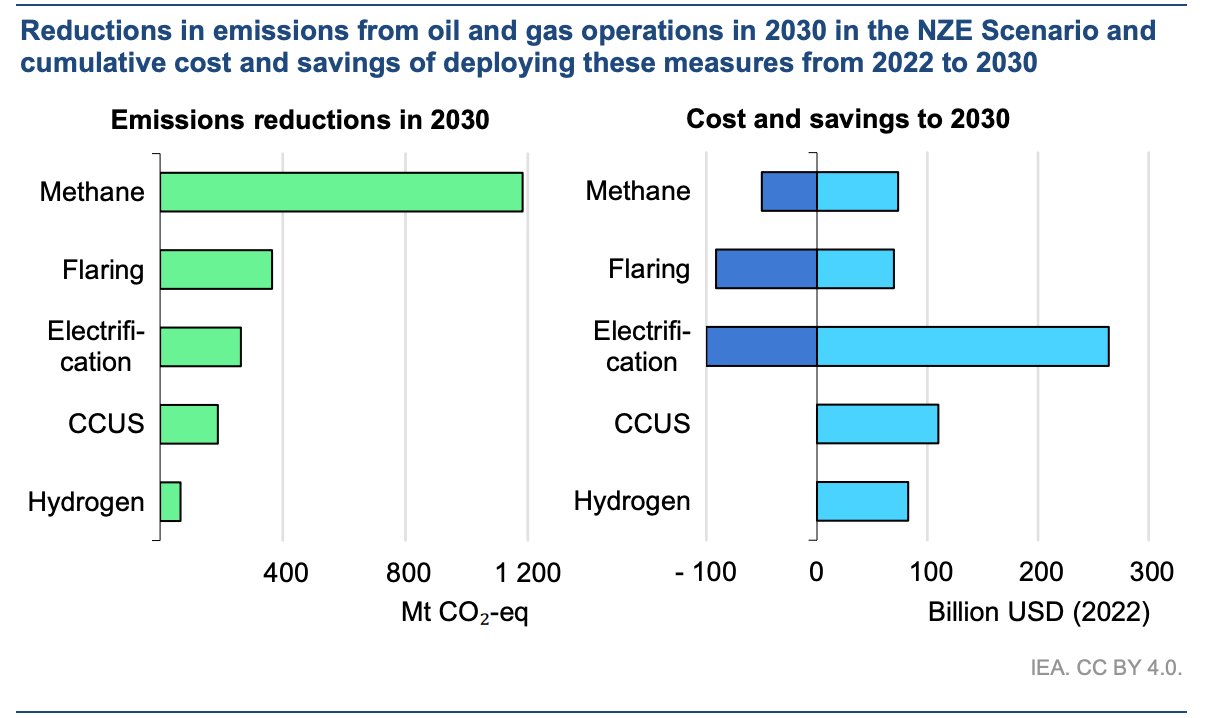

The IEA estimates that the emissions intensity of oil and gas activities need to fall by 50% by 2030 in order to meet the world’s 2050 net zero target. According to the agency, some of the strategies the sector could use to achieve this include tackling methane emissions, eliminating non-emergency flaring, electrifying upstream facilities with low-emissions electricity, equipping oil and gas processes with carbon capture, utilisation and storage technologies, and expanding the use of hydrogen from low-emissions electrolysis in refineries.

These solutions may present their challenges, but most are already commercially available and economically viable. In 2019 already, McKinsey estimated that 90% of known technological solutions to decarbonise the industry are “within the grasp of operators at a cost of no more than US$50/metric tonne of carbon”. All in all, oil and gas companies would need to make an upfront investment of US$ 600 billion to halve the sector’s emissions by the end of the decade.

But despite the urgency of the situation, a series of recent decisions by oil and gas corporations would suggest that climate is the least of their current concerns. In February this year, BP announced plans to lower its 2030 Scope 3 emission reduction targets from the 35-40% pledged in 2020 to 20-30%, while increasing investments in oil and gas by around €1bn per year in the same timeframe.

In June, Shell went back on its pledge to cut oil production by 1-2% each year until the end of the decade, deciding instead to maintain production and invest US$ 40 billion in oil and gas production between 2023 and 2035. The move caused tensions internally, with employees expressing “deep concern” in a September letter to the CEO. “For a long time, it has been Shell's ambition to be a leader in the energy transition. It is the reason we work here,” said two employees from Shell's low-carbon division.

And in August, Canadian company Suncor Energy announced a refocus towards the “fundamentals” – and away from the energy transition – that includes the scrapping of its Chief Sustainability Officer role, currently held by Arlene Strom.

These controversial decisions come at a time of mounting pressure for companies and governments to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels. Environmental activists are fighting – including in court – against the development of new oil and gas projects; UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres recently called for the phasing out of oil, coal and gas to avoid a climate “catastrophe”, and even the IEA’s net zero scenario states that no new fields can be developed if we are to meet the target. So what’s the logic behind them?

Record profits and a refocus on supply security

One thing is for sure: it’s not a cash flow problem. In its 2023 oil and gas industry outlook, Deloitte notes that the sector “earned record profits in 2022, providing ample cash flow to fund their strategies in 2023”.

The reduction of supply to meet the pandemic-related drop in demand, combined with a sudden demand increase as the Ukraine-Russia war disrupted gas supplies, sent prices skyrocketing last year. This led to a record US$ 4 trillion in revenue, up from an average of US$ 1.5 trillion in recent years. Meanwhile, profits for top Western oil and gas companies including BP, Chevron, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Shell and TotalEnergies reached US$ 219 billion.

In this context, the US$ 600 billion required to reduce the sector’s energy intensity by half before 2030 seems like a small ask. “This is 15% of the windfall net income the industry received in 2022,” noted the IEA. But instead of investing record earnings into their net zero transition, oil majors have decided to put it towards more fossil fuel production.

“I think what we have seen happen with energy prices has reinvigorated the belief that there is still a long-term need for oil and gas, and most definitely a short-term opportunity. Given that it is still their core business and will remain so for many years, they are, in their opinion, doing what any business is expected to do when demand for its product goes up. It appears achieving net zero sooner rather than later is a lower priority for the time being,” Colin Gault, Head of Product at energy software provider POWWR, told CSO Futures.

Indeed, speaking to investors on Shell’s 2022 earnings call, CEO Wael Sawan explained: “Oil and gas will continue to play a crucial role in the energy system for a long time to come, with demand reducing only gradually over time. Continued investment in oil and gas is critical to ensure a balanced energy transition, because of (...) growing energy demand (...), as well as natural decline rates and severe underinvestment in recent years.”

Perhaps another reason can also be found in Deloitte’s calculation of the financial impact of investing in low-carbon technologies. In its 2022 ‘Striking the balance’ report, the consultancy noted that going green “can reduce the overall internal rate of return of an oil and gas company by 2% to 4.5%”.

Chevron’s proxy statement ahead of its 2023 annual general meeting suggests that oil companies are simply unwilling to make that sacrifice. The board of directors recommended against a stockholder proposal to set a medium-term absolute Scope 3 emissions reduction target, saying it would require “shrinking Chevron’s business”. “Your board does not believe that committing to reduce Chevron’s absolute Scope 3 GHG emissions is in stockholders’ interests, nor should it be Chevron’s responsibility,” the proxy statement added. In the end, the proposal was rejected with only 10% of votes in favour.

Oil and gas decarbonisation: Impact for the sector and beyond

It’s not clear what individual companies’ scaling back of climate ambitions will mean for the sector as a whole. The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) gathers the CEOs of Aramco, BP, Chevron, CNPC, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Occidental, Petrobras, Repsol, Shell and TotalEnergies in an effort to “lead the industry’s response to climate change and accelerate action to a net zero future”. One of the group’s first concrete initiatives was a commitment to cut methane emissions to an intensity of 0.25% of total fossil fuel production by 2025, compared to 0.32% in 2017. Together, members achieved this target in 2021, and subsequently launched the new Aiming for Zero Methane Emissions initiative with the goal of reaching “near zero methane emissions from their operated assets by 2030”.

The OGCI declined to comment on how some of its members’ recent decisions will affect the group’s collective ambitions.

“On this evidence, the trajectory to net zero for the oil and gas companies will now have to be much steeper between 2030 and 2050. That will make it more challenging. It will also impact cumulative emissions, which is what really needs to slow down,” said Gault.

Even if the backtracking doesn’t end up affecting oil majors’ 2050 net zero targets, it is likely to have a negative impact on their interim targets. “If the bulk of your investments remain tied to fossil fuels, and you even plan to increase those investments, you cannot maintain to be Paris-aligned, because you will not achieve large-scale emissions reductions by 2030,” said Mark van Baal, founder of activist shareholder group Follow This.

It could also derail oil and gas investors and customers’ medium-term decarbonisation plans. Already, several shareholders have expressed concern over these decisions.

“Sustainability goals being set by organisations in all industry sectors are dependent on being able to decarbonise their energy consumption. That is put at risk when the sector dials back their ambitions to transition away from fossil fuels. By reducing ambition and continuing to invest in fossil fuels as opposed to low carbon alternatives we could unfortunately see a slowing down of the global effort to decarbonise. These companies have a lot of influence and the messages this sends out could be picked up by others as an indication that they too should alter their commitments to net zero,” warned Gault.

While oil majors’ refocus on fossil fuels could lower the availability of low-carbon energy products in the short and medium term, it may also create an opportunity for energy companies with stronger green ambitions to position themselves as low-carbon leaders. “Those companies could see the scaling back of others as an opportunity to move even faster,” he added.

Member discussion