Carbon offsets: a new risk for Chief Sustainability Officers?

Carbon offsets risks are growing after a series of scientific reports questioning their efficacy – but there are some things CSOs can do to mitigate them.

“Most projects have not significantly reduced deforestation.”

That’s the conclusion of the latest scientific study of the actual impact of forest carbon offsets, for example, published in Science last August. Researchers looked at 26 projects in six countries on three continents, all claiming to decrease carbon emissions from forests by avoiding deforestation through the REDD+ initiative.

These generally feature improved forest monitoring, local stakeholder engagement and the promotion of sustainable practices – and represent 65% of land-use carbon offsets sold in carbon markets. Their carbon reduction potential is calculated based on observed forest cover and projected deforestation in the absence of such projects, but research results estimated that “only 5.4 million (6.1%) of the 89 million expected offsets from the REDD+ projects would be associated with additional carbon emission reductions”.

Understanding additionality

One of the key elements in assessing the quality of a carbon project revolves around the concept of additionality. Put simply, a project is additional if it can demonstrate that it would not have gotten off the ground without the added funding provided by carbon credit sales. Most carbon credit standards include additionality assessments, but it’s important for companies to get familiar with their specific methods and criteria to ensure that carbon credit investments drive additional impact.

Before that, other recent investigations found most forest carbon offsets flawed or even “worthless”, as summarised by the infamous Last Week Tonight segment on the topic. For Chief Sustainability Officers and their teams, such critiques emphasise the extent to which carbon offsets risk causing reputational damage – as well as putting their utility in question.

Demand for carbon offsets dropped for the first time in 2022, and corporate giants including EasyJet and Nestlé have reduced their reliance on offsets to achieve their net zero goals. While putting more decarbonisation budget towards reducing rather than offsetting carbon emissions is generally seen as the right thing to do, many market experts consider carbon offset demand as crucial to support the sustainable development of poorer countries.

“The real point of the carbon market isn’t necessarily to allow companies to meet their climate targets: it’s to channel funding to where it’s needed in the Global South. There needs to be a paradigm shift in that debate,” Phil Brady, EVP, Marketing and Communications at Emergent Climate, a non-profit set up in 2019 with the goal of bringing an end to deforestation, told CSO Futures.

Additionally, a June 2023 Trove Research report analysing the emissions performance of 4,156 companies over the last five years found that “companies that are material users of carbon credits decarbonise twice as fast as those that do not use carbon credits”.

According to the authors, this has a lot to do with the mere act of voluntarily attaching a price to emissions. “This results in an annual cash expenditure in their budget, which companies then try to reduce. The opportunity to reduce costs then helps to strengthen internal business case(s) to reduce emissions in that firm’s investment / budget approval processes,” said the report’s authors.

So how can companies support the purpose of the voluntary carbon market, avoid reputational risks and drive positive impact through carbon offsets?

Carbon offsets risk: Market integrity efforts mount

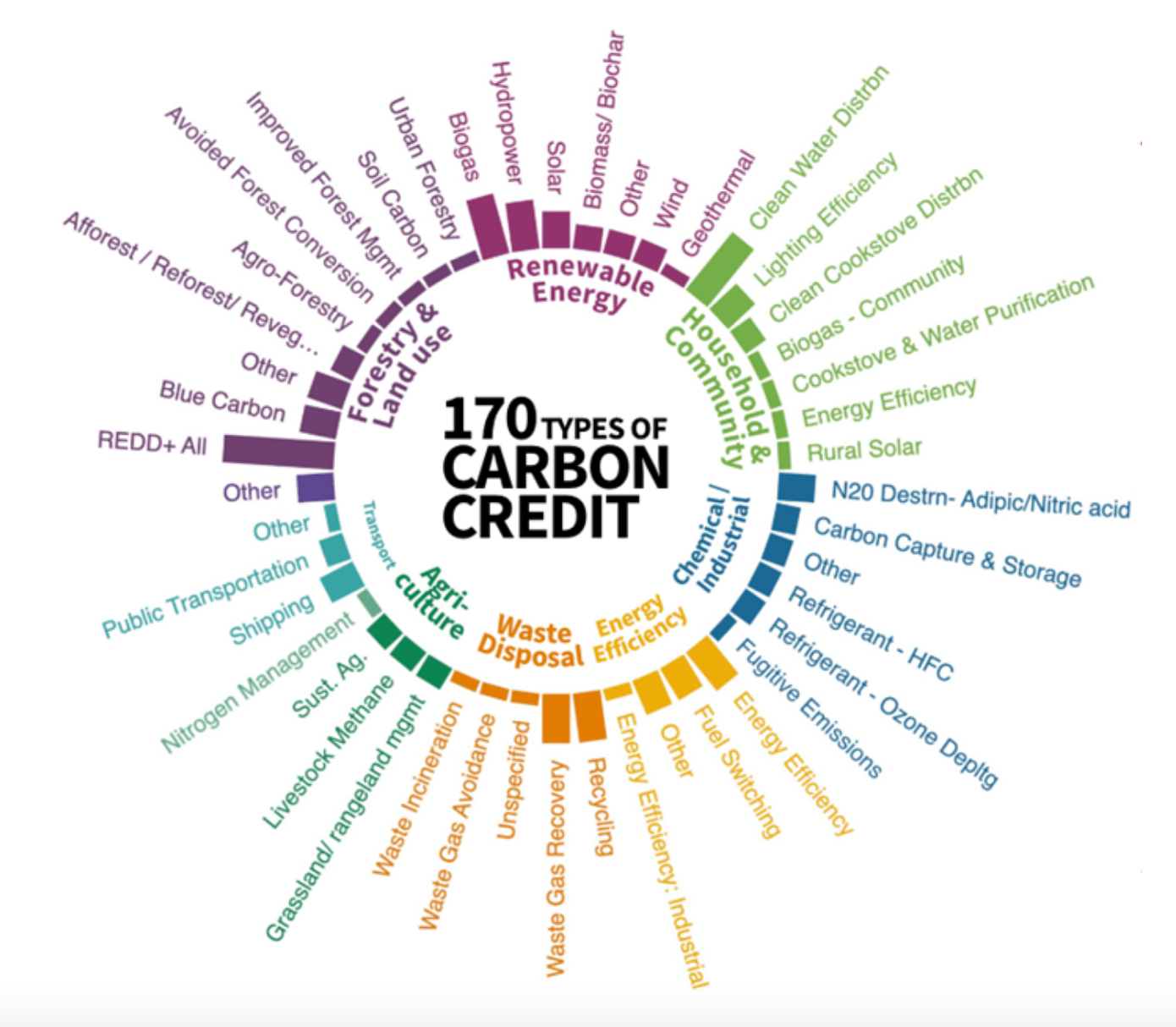

To mitigate carbon offsets risk, CSOs need to understand the different types of projects that can issue carbon credits, and where the forest projects being criticised sit within that ecosystem. Ecosystem Marketplace has identified 170 types of carbon credits, spread between eight categories: forestry and land use, renewable energy, household and community, chemical or industrial projects, energy efficiency, waste disposal, agriculture and transport.

Most of the backlash concerns rainforest protection offsets, with the wide majority being categorised as REDD+ and certified by Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard (VCS).

These are just a fraction of the range of carbon offsets on the market, but they are also one of the most popular. For that reason, the type of negative report mentioned above tends to reflect badly on all carbon offsets, and on the voluntary carbon market as a whole.

Concerns about the integrity of carbon offsets and the projects that produce them are not new: the voluntary carbon market is still young and operates under little to no government oversight. Its lack of transparency and standardisation makes it prone to miscalculations and abuses. But over the last few years, market stakeholders have come together in different ways to improve integrity and standardisation.

On the demand side, the Voluntary Carbon Markets Initiative (VCMI) is working to ensure that the corporate use of carbon offsets generates real impact for communities and the environment. Its Claims Code of Practice, released in June 2023, lays out a number of actions corporate buyers must take so that their use of offsets increases overall greenhouse gas mitigation, rather than substituting for existing actions.

Meanwhile, on the supply side, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) published a set of criteria to assess the quality of carbon credits, called the Core Carbon Principles (CCPs), in July 2023. These include governance, impact and sustainable development elements, and come with a thorough assessment process.

“The challenging part about the carbon market is there is no one right and perfect answer to any of these questions. These are intangible commodities, and their value is the value that the policy gives them; they’re not tons of gold, you cannot weigh them. So it means that the policies and the methodologies that we use in this space matter a lot,” commented Alexia Kelly, Managing Director, Carbon Policy and Markets Initiative at High Tide Foundation and ICVCM Advisor.

ICVCM has started the process of evaluating standard-setting organisations (the likes of Verra and the Gold Standards) against the CCP’s governance criteria. Once approved, these will be able to submit their carbon crediting methodologies for ICVCM’s working groups to review. Internal and external experts with specialised knowledge of the specific categories will determine which project types should be fast-tracked for approval, and which will require deeper assessment. Asked by CSO Futures whether controversial forest projects were likely to belong to the latter group, Kelly responded that it was “too early to say”.

For those fast-tracked project categories, ICVCM hopes to make the first CCP-labelled carbon credits available to the market by January 2024, but this is not even what Kelly is most excited about.

Instead, she pointed to a set of 10 Continuous Improvement Work Programmes announced by the Council this past July: “Those address issues that are really important to the future of the market, and for which right now we don’t really have a centre of gravity. Application of digital remote sensing technology, for example, is a game-changer in helping us do better, more rigorous and more robust baseline construction, project evaluation and ongoing monitoring for reversals. But all of the standards are sort of using it in different ways, so one of the things we want to do under the ICVCM is bring together a cross-market conversation around what the future and role of this technology is for the market and how we can start to take a more standardised approach to some of these key issues,” she added.

Towards jurisdictional forest carbon projects

The most problematic types of offset tend to be the ones that claim to avoid deforestation. Forest projects’ flaws come mainly from the way they calculate carbon reductions: the Science study authors, for example, pointed to the fact that deforestation baselines used to calculate CO2 savings could be “opportunistically inflated by profiteers seeking to maximise the volume of offsets issued by a project”. A recent case study led by MIT, IBM and BBVA showed promise for the use of satellite data and AI to better estimate the sequestered carbon of such carbon offset projects, but more work is needed to make accurate assumptions.

They also face a high risk of leakage: the plot of land covered by the project may indeed be protected from deforestation, but there is no guarantee that deforestation won’t increase in neighbouring areas.

The CCPs may help companies identify the most impactful of these projects, but another avenue seems to offer much more potential. Emergent Climate believes that the end of deforestation can only be achieved through jurisdictional forest projects, that is, government-led forest protection schemes developed at national or subnational-scale.

“If you look at the urgency and enormity of the climate crisis we’re facing, we won’t deliver the finance needed at the scale required to halt tropical deforestation and reduce emissions without working at a jurisdictional scale,” Brady explained.

Jurisdictional schemes are run in countries or states with at least 2.5 million hectares of forest, and have to demonstrate reduced deforestation across the entire area, via compliance with the ART TREE standard.

Emergent is also behind the LEAF Coalition, a public-private initiative meant to send a strong demand signal for jurisdictional forest projects. Brady explained that these national-scale projects are still in their infancy, particularly in terms of demand from corporate buyers. To this day, the first and only private sector transaction occurred between Guyana and US oil and gas company Hess Corporation in December 2022. According to the agreement, Hess agreed to purchase 37.5 million carbon credits for a minimum of US$750 million between 2022 and 2032.

Through the LEAF Coalition, sovereign and corporate buyers abiding by a set of integrity criteria can make forward purchase commitments of jurisdictional carbon credits from the year 2022 to 2026.

“The whole point is that we need to mobilise more money and channel that to developing countries to give them the finance to put in place the programmes needed to deliver on their NDCs. The public sector just doesn’t have the capacity to do that, we need to mobilise the financial might of the private sector to do that,” added Brady.

A number of NGOs and standard-setting organisations, including the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTI), are encouraging companies to purchase jurisdictional forest carbon credits as part of their Beyond Value Chain Mitigation (BVCM) strategies. Written by eight non-profit organisations, the Tropical Forest Credit Integrity Guide 2023 recommends that companies “rapidly shift demand toward credits originating from jurisdictional-scale programs”, including by signalling demand through forward purchases.

For Kelly at the High-Tide Foundation, both project-based and jurisdictional forest programmes have a role to play in ending deforestation. “In a properly designed system that enables them to nest together, interact and work more constructively to accomplish their ultimate and shared objective, project-based and jurisdictional activities are complementary and mutually reinforcing,” she said, adding that the conversation around how to design such systems will continue to evolve and unfold over the course of the next few years.

Member discussion